If up’s still up and down’s still down

Won’t you tell me where the hell am I?

I’m getting threats on top of threats from within

I’ve been bullied, bullied, bullied by a parallel time

- Ryan Davis, "New Threats from the Soul"

I gotta to be honest, this year was a little underwhelming in terms of new music, or maybe it only seemed as such because it came on the heels of a stunning year for a slew of my favorite artists, including Father John Misty, Sturgill Simpson, Adrienne Lenker, and Vampire Weekend, all of whom released, arguably, the best work of their careers. My tastes skew towards the not-quite-mainstream, and the albums released in this space in 2025 felt like they hit a glass ceiling in the Room of the Nearly Great. Jeff Tweedy’s Twilight Override, Colter Wall’s Memories and Empties, and Mac Demarco’s Guitar, for instance, are all solid albums, but I’d hesitate to call any of them career-defining (though perhaps Tweedy’s comes close). I’ve been informed by tastemakers in high places, like Anthony Fantano and Pitchfork, that Geese’s Getting Killed deserves to be included in the Pantheon of the Truly Great, but it’s an album that hasn’t fully landed for me yet, and I’m not going to feign adoration just to seem cool, even though I’ll admit that Geese is a band I’ve been wanting to fully embrace for some time now. I could see how I might someday consider their new album a classic: there are flickers of brilliance refracting through the noisy weirdness and the pained yowling, and I’m already sold on a few of the tracks, specifically “Au Pays du Cocaine,” which is just punishingly beautiful, but the rest of the album may need a couple hundred spins before it all clicks into place. Or maybe I’ll just have to gradually accept that Geese and I weren’t meant to be. So it goes.

Instead of half-heartedly drumming up a list of my favorite albums from a subjectively ho-hum year, I’m going to focus on one song that’s so great it deserves an indulgent 2,000-word deconstruction. That song is “New Threats From the Soul” by Ryan Davis and the Roadhouse Band, off an album of the same name. Davis’ star has risen immensely over the past year: he earned himself a write up in The New Yorker, and the almighty Pitchfork ranked “New Threats” the fifth-best song of 2025, which feels like a gratuitous slight. I’ve listened to the four songs ahead of it, and all of them are good, but none are as finely-honed or well-rounded as Davis’ masterpiece; I say this as someone who loves the top-ranked song, “Love Takes Miles” by Cameron Winter (who by the way, fronts a little band called Geese). The greatness of “New Threats” lies in the way that Davis manages to compress basically all of my favorite aspects of songcraft into a single track: over the span of nine-and-a-half minutes, we get Bob Dylan’s lyrical world-building, David Berman’s wry self-deprecation, Pavement’s blend of detachment and authenticity, Radiohead’s building-towards-a-climax energy, and on top of all that, the simple yearning of classic country music and the hooky chorus of a Top 40 hit. On paper, these disparate parts add up to something truly abysmal, yet Davis patches it all together into a hilarious, inspirational, and highly-listenable quilt.

Indeed, perhaps the most surprising thing about “New Threats” is its eminent catchiness: throw it on for your non-music-loving friends and you may find them mindlessly tapping along with the rhythm. There are other really good songs on this Nearly Great album, most notably “The Simple Joy,” but none can match the title track in terms of sheer earworminess and forward propulsion. If any song off this record was going to garner radio play (and let’s be clear, none of them will), it’d be this one: steadied by a prominent drum beat, it comes floating in on dreamy saxophone and steel guitar tones, like a jester tap-dancing on a cloud. This finger-snapping intro leads us into the first appearance of Davis’ twangy baritone, and from the moment he opens his mouth, it’s unclear whether he’s embracing the country music ethos or lampooning it. This tension doesn’t get any clearer as the song progresses, which is to its benefit: one of Davis’ biggest strengths is his ability to honor the tropes of traditional country while maintaining a self-awareness about its absurdity. By the time the first of many (varied) choruses comes around, it’s clear that Davis is right in his wheelhouse:

I thought that I could make a better life with bubblegum and driftwood

Her sweet nothings were nothing more than debts I would owe

She once said that nothing could make her feel quite as loved

as one early morning kiss could

But I’ve been up late one too many nights while I let myself let her go

And for who I’ll never know, right then and there that’s where we begin

These new threats from the soul.

It’s writerly lyrics such as this that make “New Threats” feel like something John Prine or Townes Van Zandt might have written had they earned a master’s degree in creative writing. Davis, when embodying his purest country form, deserves at least a passing mention in the same breath with some of the most revered alt-country artists. It makes me wish that he’d stay more firmly planted in this tradition instead of venturing into some of his more avant garde stuff, which, while good, sometimes feels a little unmoored. The headiness of Davis’ lyrics work best, I think, when grounded in a foundation of (relatively) straightforward country/rock instrumentation. He has a strong history of writing twangy off-kilter bangers, like “If You Don’t Show Me,” which he recorded in 2018 with his old band, State Champion, and features his patented farcical lyricism:

Lost my soul on the second floor of a gentleman’s hall in Tijuana

That’s the kind of thing that goes on in those places

so I’m trying not to let it bring me down

The manager said that if it turns up, yeah, he’s gonna send it on home to me

But I’m living in my poncho, so I give him your address and leave

How am I supposed to let you go, if I don’t know if my soul’s been received?

That verse, to me, is another example of something that could’ve been pulled straight from the liner notes of a John Prine album, or perhaps even a southern gothic short story collection. Davis is a master at singing in grammatically correct full paragraphs, which is no easy feat: it takes patience to come up with literate lyrics that don’t feel pretentious, or bog down the flow of the song. Davis’ words are willfully smart but not pedantic, and they succeed in delivering an emotional thrust because they feel like earnest expressions from a searching soul, not pretentious musings from someone trying to prove their intellectual superiority. As Davis deploys one great line after another (example: “I will never be anything/other than a caged bird swinging from a chain-swing/whistlin’ for my payseed, peckin’ on a W9”), it’s clear he has a novelist’s skill for precise phrasing, and that he’s a guy who makes countless revisions until his delicate web of creation hangs together just so. He told The New Yorker that he finds writing lyrics “virtually impossible,” then added: “I’ve always envied people who can just come home from work and pick up a guitar and write a song, and it ends up being something people wanna hear. But I have to really drive myself to the brink of lunacy to make a chorus that works for me.” His lunacy, it seems, is our gain.

The song moves like a series of waves that crest and recede a little differently each time, and the listener is helpless out there in the water, minding the strange undercurrents while trying (and failing) to predict when the next wave will come rolling in. No two refrains are quite the same, even if at the onset it seems like they might be.

Another thing that makes “New Threats” such a fascinating anomaly is that, even though it’s nearly 10 minutes long, it never feels repetitive or as if it’s dragging on. It’s easy to get that ears-glazed-over feeling during lengthy songs if there’s no variance in structure, and this, I think, is what lifts “New Threats” from an epic lyrical odyssey in the mold of “Desolation Row” or “I Dream a Highway” into a stratosphere all its own. The song moves like a series of waves that crest and recede a little differently each time, and the listener is helpless out there in the water, minding the strange undercurrents while trying (and failing) to predict when the next wave will come rolling in. No two refrains are quite the same, even if at the onset it seems like they might be. As Amanda Petrusich put it in Davis’ New Yorker write-up: “Nothing is exactly where you expect it to be, and nothing stays still for very long.”

Davis matches this persistent lyrical and structural novelty by varying his vocal delivery between the aforementioned countryish baritone and a sort of anthemic belting, the latter of which reaches a climax at the 7:30 mark, when he brings it all home with a throaty howl that feels like a final, towering wave pummeling us out of nowhere. He sings: But can one really blame the soul?/The strange positions I have put it in/have led to mismeasurements between the place where I am/and the place that I could’a been. It’s a high-water mark for the year in music (Pitchfork’s fifth-best ranking be damned), and perhaps the peak of Davis’ musical career, the moment all of his other work had been rambling towards. Just a few years ago, he was working at a restaurant and mourning the dissolution of State Champion, trying to figure out what the hell to do next. “I was just stuck,” he told The New Yorker. “I was feeling really disconnected from everything. I didn’t know what the path forward was.” Safe to say, he’s found it.

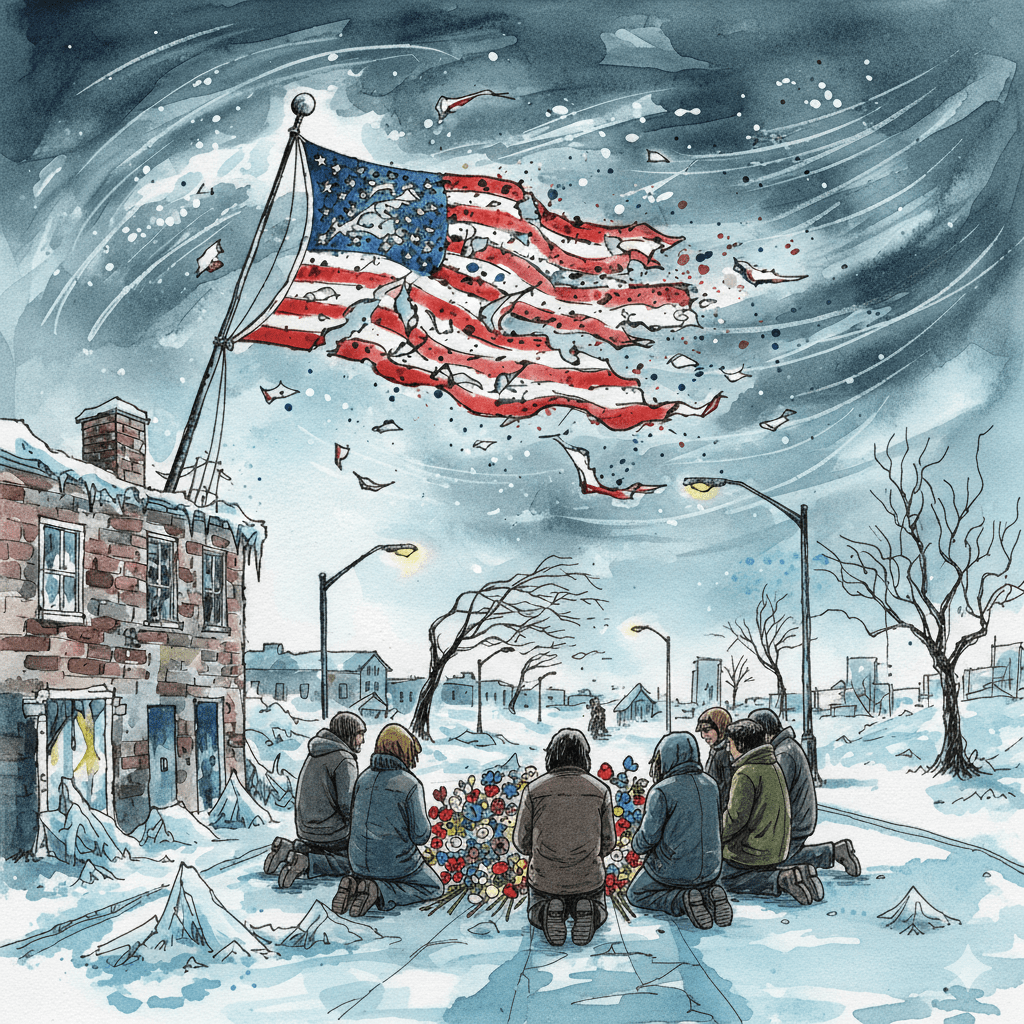

“New Threats” struck me in a profound way not only because of its technical brilliance, but also because its core message reached me at a specific moment in my life; it was, truly, a right-song-at-the-right-time situation. Davis and I are both elderish millennials, and we’re facing similar internal dilemmas as we march towards middle age: principally, the feeling that our lives are beginning to calcify, and that our weaknesses, of which we’re painfully self-aware, can sabotage even our best-laid plans. We’re coming to grips with the fact that certain futures we’d envisioned as idealistic 20-somethings may never materialize, that the door to them is closing, if not already shut. This is the hard-won moral at the nexus of Davis’ magnum opus: as we grow older, the biggest threats to our happiness come from within, and we must find a way to manage them and, in doing so, learn to live with our messy selves, because even though our hair is thinning and the bags under eyes are deepening, we still have another 40-60 years to go, if we end up being so lucky.

This is the hard-won moral at the nexus of Davis’ magnum opus: as we grow older, the biggest threats to our happiness come from within, and we must find a way to manage them and, in doing so, learn to live with our messy selves, because even though our hair is thinning and the bags under eyes are deepening, we still have another 40-60 years to go, if we end up being so lucky.

When Davis sings, near the end of the song, about being “bullied by a parallel time,” I get it, because I often feel the ghosts of alternate timelines haunting the corners of my psyche, teasing me with visions of other lives I could’ve lived, other people I could’ve been. There’s a sense of loss in choosing a path, or having it chosen by inaction, and Davis battles this feeling for the majority of the song. Yet by the final refrain, he’s reached a level of acceptance that feels earned, given the journey he’s just shepherded us on. He sings: Sliding doors have slid and now all I can do/Is do my best to control/The cruel transferences from the mirror world/And new threats from the soul. The experience of aging may feel like a sliding door being slid shut, over and over again, but it’s also about learning to appreciate the timeline we’re currently inhabiting: not the mirror world, but our actual lived-in reality. Davis is aware that, as he puts it near the centerpoint of the song, it’s “hard to know sometimes if I’m on the right course,” but he’s also wise enough to recognize that sometimes the best solution to existential uncertainty is to ramble on, pesky transferences be damned, toward the fading yet resilient white light of yet another tomorrow, and another one, and another one.

Leave a comment