I wrote a lot about my son when he was first born, mainly because it’s the only thing I could write about. The decision was beyond my control, not only because other things suddenly didn’t seem as important, but also because I spent most of my waking hours taking care of him. The three of us, Caitlin, Conley, and I, lived in rural Western North Carolina, out where the asphalt turns to gravel and it’s not uncommon to see someone riding a horse down the road. It was the height of COVID isolation, so the only time we left the house was for doctor’s visits and grocery runs, the latter of which never included Conley, for fear of getting him sick. We started calling him our holler baby…our uncivilized, socially-distanced holler baby, whose entire universe consisted mostly of the 1,400-square-foot main floor of our brick rancher. It could get stuffy in there at times, suffocating, even, so after staying up most nights tending to his g-tube feeds, I’d sometimes ascend the small mountain behind our house and sit alone on a soft log or hunk of dirt, inhaling the cool air with the hope that it’d bring me some semblance of centeredness, which it always did, temporarily.

I also wrote, a lot, because writing helped establish an illusion of control over an uncontrollable situation. I recently re-read some of the stuff I penned during this early period of Conley’s life, and the main thing that stood out to me was the myopicness of my words: it was as if everything else had slipped out of the frame (other than, maybe, COVID), and the only thing left was our son: our beautiful, uncommon, g-tube fed son, and the ways in which his presence was fundamentally reshaping our experience of the world. It’s well-known that having a child significantly alters the brain chemistry of the woman, but it changes the man’s brain, too: “dad brain,” as it were, defined by a drop in testosterone and an increase in dopamine and oxytocin, which promotes bonding and a sense of connectedness. I felt this shift acutely in the dreamy months after Conley’s birth, when it seemed right and true and, frankly, enough, to cocoon ourselves in our country home and tend to his every need; it was as if I was realizing some cosmic destiny I hadn’t even known was mine.

Other new fathers have experienced this feeling of divine purpose, too: country artist Sturgill Simpson, one of my favorites, wrote an entire album as tribute to his newborn son, the first song of which features the lyrics: “Wish I’d done this 10 years ago/but how could I know/that the answer was so easy?” The answer to what exactly? To cosmic aimlessness, perhaps, at least that’s how I interpret it, because when my son was born, I, too, felt a new chamber in my heart open, though I worded it in a slightly different way: “Kim Jung Un could’ve launched a nuclear warhead into the heart of New York City and I wouldn’t have known, or had I known, wouldn’t have cared, for at least a week.” Manhattan could’ve been leveled thanks to a psychotic North Korean autocrat and even that wouldn’t have been enough to shake us from our single-minded parental trance; such was the intense devotion to this creature who’d fallen into our soft arms from the infinite darkness of pre-existence.

Manhattan could’ve been leveled thanks to a psychotic North Korean autocrat and even that wouldn’t have been enough to shake us from our single-minded parental trance; such was the intense devotion to this creature who’d fallen into our soft arms from the infinite darkness of pre-existence.

Conley turns five in January, which is just insane, really. The world has opened up in the half-decade since he was born, both in general and for him personally: for starters, people can go out in the world without masks on, something that felt impossible during the darkest days of COVID. We also moved to Staunton in 2023, to be closer to family, and in the wake of that relocation, Conley has progressed from his holler baby form into a mostly civilized four-year-old in a typical pre-k class, another thing that felt impossible just a few years ago, due, at least partially, to his anatomical differences. These differences (no ear canals, clenched hands, serpentine feet, small ears, among other things) stem from a genetic disorder called Van Maldergem Syndrome, three words we uttered to a nauseating extent early in his life, but haven’t said much recently, which is a testament to his remarkable progress. He does taekwondo, dance, and tee-ball, which are great for his physical development, but it’s music he loves most. One song that’s gotten a lot of play for us recently is “Brain Stew” by Green Day, which frontman Billie Joe Armstrong apparently wrote in the throes of sleep deprivation after the birth of his first son. Sometimes Conley and I blast it on the way to school, and I watch him in the rear view mirror as he headbangs to the crunchy guitars like he’s in the front row of Woodstock ‘94. He wouldn’t be able to hear the music without the miracle of BAHAs (bone-anchored hearing aids, or his “ears,” as we call them), which he’s worn on a headband since he was only a few months old. I remember being terribly worried, in the days after we learned that he was technically deaf (the world sounds underwater to him without his “ears”), that he’d never be able to experience the simple human joy of music; only in retrospect did it become clear that those worries were unfounded, and I try not to go too long without reminding myself how grateful I am for that.

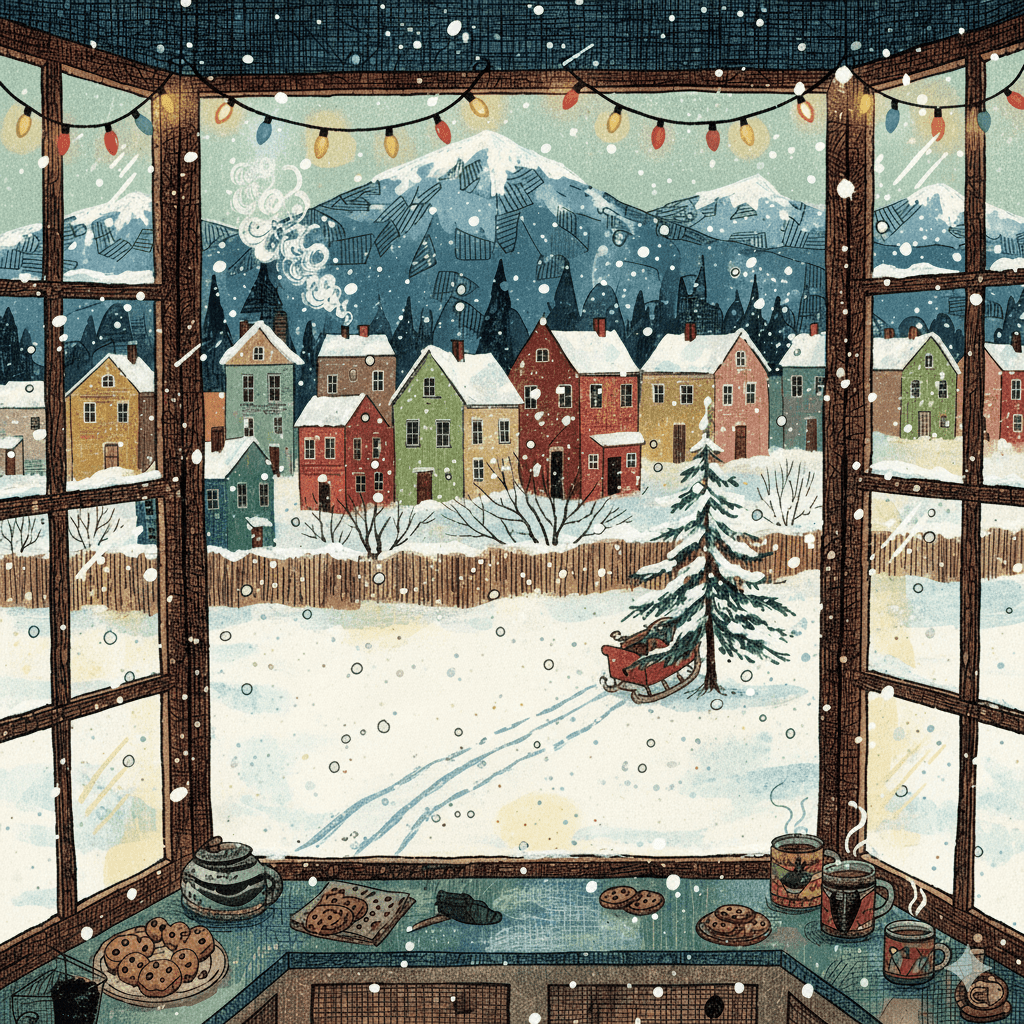

As I write this, Conley is supposed to be napping in his room, but instead he’s singing “Jingle Bells” at full volume while inserting random lyrics from “Winter Wonderland,” creating an admittedly catchy little mash-up. I gaze out of the wraparound windows in our kitchen, down onto the backyard, which is covered in a soft down comforter of white with smooth tracks cut through it, revealing the grass and mud underneath. It’s the first snowfall of the season, and we were out there this morning, plump in our winter coats, careening around the yard in a sleigh Conley got during his second Christmas, back before he could even walk by himself. He didn’t take his first steps until he was almost three, but he was out there today, one month shy of his fifth birthday, helping me push the sleigh up the hill. His chubby cheeks were honeycrisp, and his hands were pink and cold under thin mittens, but all he wanted to do was move his body through the pure white powder for a little while longer. Snowflakes floated onto our heads like soft confetti, and the whole scene was transcendent in the way that all fleeting, mundane moments of parenthood can be viewed as transcendent with the right mindset, which usually requires several cups of coffee and a hearty breakfast.

Another thing that’s changed over the past five years is that Caitlin and I have snapped out of our caregiving trance: there is an outside world now, and we most definitely would care if an atomic strike incinerated one of the boroughs. The hazy dopamine days of Conley’s early life have given way to the grinding repetition of parenthood, which (surprise!) isn’t always transcendent, is, in fact, often maddening, because children are legit wild animals. This untamed volatility can make parents feel like they’re strapped to a pendulum in which joyous highs provide the momentum to swing your child, and by proxy, you, into the depths of an equal-and-opposite foul mood later on.

Point-in-case: after having what I thought was a pretty tender morning out in the snow, Conley informed me that he no longer loved me, and that he wanted me to go away. He’s expressed a lot of disdain for me recently, an attitude shift that I’m chalking up to his Oedipal Phase, and also the fact that I’m the self-branded TV Czar who often makes him turn off Gabby’s Dollhouse or Toy Story or whatever bright loud thing he’s watching that day. Sometimes when I walk into the room, he’ll grunt some version of GO AWAY, YOU’RE A BAD MAN, I DON’T WANT YOU. I was fine with these verbal attacks at first, because I like to think I’m a moderately well-adjusted adult, but a man can only absorb so much abuse from his own offspring before it starts feeling like his heart is being roughly chopped for a stew.

I often think that parenting a young child must be a lot like the experience of military boot camp: it’s almost always hard in the moment, and most of the joy you’re able to wring from it comes from the realization of its transience and the recognition that you’re pushing yourself further than you ever thought you could go. Once it’s over, you’re proud to have done it, because it was demanding and grueling and filled with mud and sweat and, to a greater or lesser extent, poop, but, by God, you did it, you prevailed, and it’s the most rewarding thing you’ve ever done in your life; or if it’s not the most rewarding thing, it’s at least one of the most memorable, because what other period of your existence was filled with so much emotional volatility and variance, the highest possible highs and the lowest possible lows?

I think back to those early months of Conley’s life, when he was the only thing I could write about, when I’d lie on the couch beside his crib in the living room because he needed to be fed via g-tube every two hours. The humidifier would be roaring to keep his nasal passages moisturized, steaming up the picture window and turning the room into a sauna. On the nights when I couldn’t trick my mind into falling asleep, I’d fingerpick an acoustic guitar while gazing doe-eyed at his smooth face and listening to his tiny baby snores, dizzy with love and sleep deprivation. Now he calls me a POOPYBUTT and a BAD MAN and throws jabs at me, and all Caitlin and I can say is where has our Sweet Baby Angel gone? Where, indeed? I’m reading a book called “Motherhood” by Sheila Heti, a work of semi-fiction in which the main character, a woman in her late 30s, agonizes over whether or not to have a child. She’s having a conversation with a friend who has two children, when she says to her:

I’m so jealous of mothers because whatever else happens, they have this person, this thing. She said: “that’s not right. I used to have things. I don’t have anything anymore. I don’t have work…my daughter is her own person. She doesn’t belong to me.” In that moment, I saw it was true: her daughter was something apart from her, not her possession or belonging at all.

This truth of parental non-possession has rang true since Conley has turned four and started pushing boundaries, asserting independence, and forming his own identity, all of which, of course, are typical for a kid his age. On my best days, which sometimes feel few and far between, I’m able to drum up a sense of gratitude at having the privilege to deal with typical four-year-old problems, instead of the more serious issues that could’ve resulted from his genetic disorder. In my best moments, I remind myself of how easily a less-prosperous timeline could’ve unfolded, how a simple twist of genetic fate could’ve led him down a difficult road of lifelong dependence. I try not to dwell on those alternate timelines, because they give me the Fear, and I also try not to allow his occasional moments of disgust at my mere existence to carry more weight than they should. The parenting pendulum will inevitably swing in the opposite direction, and that Sweet Baby Angel that I monitored during those sleepless nights in the sauna room will return in short order, because they always do, if only to disappear again.

I don’t agree with one part of what the mother-friend said in the passage from Heti’s novel, about how she doesn’t have her work, or anything, anymore. I don’t think total self-sacrifice is an inevitable result of parenthood; we can, and should, establish ourselves as separate entities from our children, just like they organically establish independence from us. Granted, it’s hard to draw this line of selfhood when you’re often positioned only in reference to your child (“so-and-so’s mom or dad”), and indeed, this will happen so much that you may forget that you have an actual name. I’m not saying it’s easy, to stake the claim of selfhood, I’m just saying it’s achievable, or at least feels achievable, though it’ll take some good time management skills and a willingness to go deeper into the well even when you’re sure that the well has run dry.

I don’t agree with one part of what the mother-friend said in the passage from Heti’s novel, about how she doesn’t have her work, or anything, anymore. I don’t think total self-sacrifice is an inevitable result of parenthood; we can, and should, establish ourselves as separate entities from our children, just like they organically establish independence from us.

The natural progression of things is for the child to move in and replace the dreams and desires of the parents, but we shouldn’t allow this to happen, can’t allow it, because it’s not healthy for us (see: the formulation of contempt and regret), and it’s definitely not healthy for the child, because they need to see their parents being people out in the world around other people, not just “mom and dad,” or a couple of POOPYBUTTS who, in the eyes of the child, simultaneously know nothing and everything. They need to know that we’re flawed and real and have the ability to stand out there on our own two feet, the umbilical cord no longer attached.

Conley has just woken up from his nap, or should I say he’s exited his room after singing Christmas carol mash-ups for an hour and pulling almost every book on his shelf down onto his bed. I’m sitting in the kitchen, writing or at least failing to, the snow still falling through the window behind me, when I hear the following conversation between him and Caitlin:

“I was dreaming about Gabby’s Dollhouse, and I pooped.”

“Gabby’s Dollhouse made you poop?”

“Yeah. I like to eat snow. I ate snow off the, um, car.”

“How much snow did you eat off the car?”

“Four.”

“You shouldn’t eat snow off the car. Cars are dirty.”

“I am a car.”

“You’re a car?”

“I’M AT A CAR, MAMA. Do you want to see my butt?”

Later that night, he’ll demand we dress him in the Buzz Lightyear costume he wore for Halloween in 2024. Back then, the sleeves extended well beyond his tiny hands, and the pant legs slipped down around his feet. Now it fits him snugly. He makes me don the Zurg mask so he can battle me in the living room, because Zurg is Buzz’s mortal enemy, and also his father, as revealed in Toy Story 2. Conley has more respect for me when I wear the Zurg mask, so after putting it on, I tell him that I’d rather be friends, to which he instantly agrees. I suggest we take a picture together to commemorate our new friendship. I lift him into my lap, and we sit there beside the Christmas tree, two peas in a pod: Michael and Conley, Zurg and Buzz, papa and son, enemy and friend, while our 114-pound chocolate lab snores in the corner of the living room on a cheap dog bed we bought off Temu (for shame, for shame).

I watch him waddle down the hallway toward his bedroom, the butt of his pajamas puffy from the Mickey Mouse pull-up underneath, and am reminded that parenthood is nothing but a series of good nights…good night to these pants that no longer fit, good night to the way he used to mispronounce certain words (like “up-pie-sow” for upside down), good night to the g-tube and the sauna room, good night to bottles and diapers and trainer potties, good night to holler baby, or to this or that version of himself as he grows older.

Conley’s nice to me the rest of the night, even after I’ve removed the Zurg mask: he tells me, before bed, that I’m the best papa and that he loves me. I tell him he’s my best son, which is something I often say, but will have to phase out on the off-chance he ends up with a brother. I watch him waddle down the hallway toward his bedroom, the butt of his pajamas puffy from the Mickey Mouse pull-up underneath, and am reminded that parenthood is nothing but a series of good nights…good night to these pants that no longer fit, good night to the way he used to mispronounce certain words (like “up-pie-sow” for upside down), good night to the g-tube and the sauna room, good night to bottles and diapers and trainer potties, good night to holler baby, or to this or that version of himself as he grows older. Heti’s mother-friend was right about one thing: a child is never fully a part of their parents; they are, and always have been, separate from us, similar, yes, but distinct. Even back when Conley was in holler baby form, he was changing in imperceptible ways, incrementally becoming a person who could stand on his own, who could help me push a sleigh up the hill in our backyard. Look at him, waddling away with his Mickey Mouse butt: good night, son, I say, or maybe whisper, but either way he doesn’t hear me, and he’s off around the corner and into his room to once again dream about Gabby’s Dollhouse, and maybe poop his pants, if one thing follows the other.

One of the essays I wrote during the Holler Baby Years was called “When Our Plane Lands.” I penned it in the middle of Conley’s five-week stint in the NICU, an innately stressful time made more stressful by COVID precautions, which only allowed one parent at a time to see their child. The bloops and bleeps of the medical machines still occasionally ring in the hollows of my mind, and I think about all the time I spent in that sanitized, nurse-ruled unit with Conley splayed across my bare chest, streaming peaceful piano versions of Radiohead songs while breathing humid air through a surgical mask, wondering if I might die from lack of oxygen. We had no clue what the future held for Conley; we were so blind and fragmented and tired and stressed and over-caffeinated that all we could do was focus on the small things that turned one hour to the next, like filling small plastic containers with breast milk or eating pre-made lunch wraps in the hospital cafeteria. We felt like ghosts of a sort, semi-transparent entities trapped in limbo between the tenuous present and the unknowable future. I wrote: “When your baby is in the NICU, nothing else exists. Life becomes a merry-go-round of hospital visits and late late nights and breast-pumping and coffee and tears and happiness that spins round and round until you’re completely disoriented and can’t remember what life was like before you had a baby in the NICU. The past is obliterated, the future is suspended, and the present exists in a strange sort of sluggish time warp.”Then I wrote the thing about Kim Jung Un obliterating New York, etc etc.

Around this same time, someone, I don’t remember who, probably one of the ever-revolving nurses, shared a poem with us that virtually every parent with a disabled child has forced upon them at some point, which is fine, because it’s a good poem, really. The gist of it is that learning that you’re going to have a kid with a disability is akin to thinking you’re taking a flight to Italy, but ending up in Holland. Holland isn’t what you were expecting, yada yada, but it has its own unique perks, like windmills and tulips and Van Gogh, I think, but don’t quote me on that. My argument, at the time, was that we weren’t even landing in Holland, because Conley’s syndrome was so rare that no doctor had even heard of it, much less knew what to expect. I ended the essay by saying that we were essentially marooned in the sky without any clue of our destination, circling the airspace and running out of fuel, on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

It continued to feel like that for a while, but here we are, five years hence, our apparent destination resembling Italy more than we ever could’ve expected. I hesitate to say we’ve landed, because there are still future unknowns, unpredictable ways his syndrome could manifest in the years ahead, but it definitely feels like we’re making our descent: I can see the Coliseum down there, and the Tiber River, too, ruins of this or that sort, and I look over at Conley, who’s seated next to me and rubbing his eyes after waking up from a nap, and he’s so sweet and docile as we hang there in the sky, but when he realizes he’s looking at me, he grunts GO AWAY PAPA, YOU’RE A BAD MAN AND A POOPYBUTT. It cuts me, hard, but I smile and tell him I love him anyway, even if he does think I’m a POOPYBUTT, and then I say hey buddy, look out the window, isn’t it so beautiful down there…isn’t it so beautiful, my best and only son?

Leave a comment