This article originally appeared in the Augusta Free Press.

There was a time, in the early 2000’s, when I loved football with such naive intensity that I wore a different NFL jersey to middle school for an entire week. This made me, undeniably, the coolest kid in 7th grade, and I was indiscriminate in my choice of players: Keyshawn Johnson, Brian Urlacher, Barry Sanders, John Elway…I wore them all with equal amounts of pride and gusto. My favorite team was the Buccaneers, and one Christmas I got a custom jersey (from Santa Claus) with “44” plastered across the back, which is the number I wore as a pee-wee league linebacker who’d hit an advantageous early growth spurt. At that point in my life, you couldn’t have convinced me there was much difference between what I was doing on Saturday mornings in rural Virginia and what Urlacher was doing on Sunday afternoons at Soldier Field. My love for football was synonymous with who I was.

Here we are, more than 20 years later, in the middle of another excessively-hyped, insatiably gambled-upon American football season, and I can’t muster even a little bit of enthusiasm. I was in the room when an NFL game was on the other day and, to my horror, couldn’t name a single player on the field. It felt like I was back in middle school, playing Madden 2001 on franchise mode at 2 a.m., scarfing down Bagel Bites and leading a team to the then-distant year of 2025, where the rosters were populated by computer-generated players. Thirteen-year-old me would be appalled at my NFL ignorance: how had I grown so out-of-touch with a sport that was once at the nexus of my existence?

Part of it, of course, is growing up: we shouldn’t care about sports the same way as adults as we did as children. As kids, sports are often our entire world, because we don’t know any better. Our perspectives widen as adults, our priorities mature. This is, of course, obvious: no one cares about a game in the same way at age 36 as they did at age 10…which, by the way, is how old I was when the Bucs fell to the Rams in the NFC Championship, a loss so devastating that I rage-hurled objects around my bedroom until my parents rushed in to (rightly) scold me, wondering what demonic force had possessed their sweet little boy. I’d never expect the adult version of myself to care about football with that toxic level of single-mindedness, but I do find it curious that I’m incapable of feeling even a little bit of excitement. I’ve been able to reframe my love of baseball within the context of adulthood. Why not football?

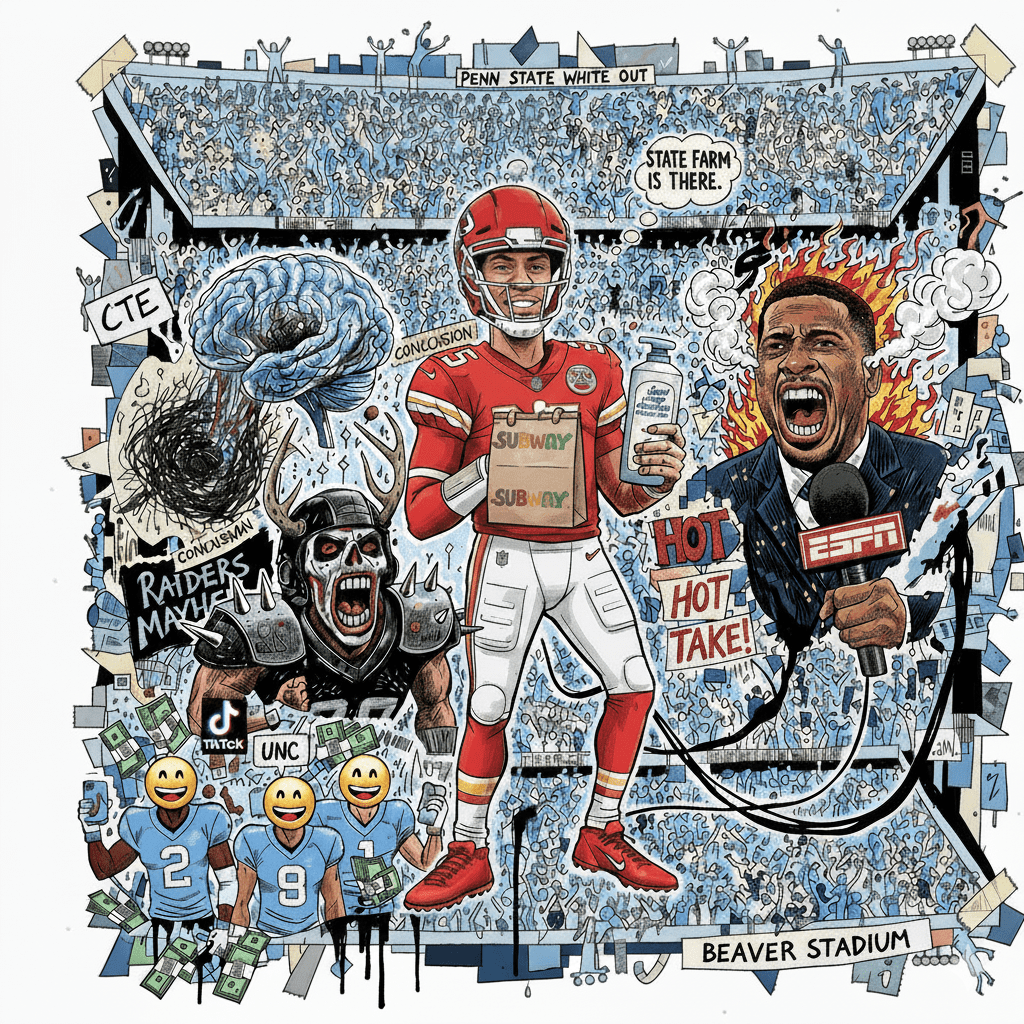

The reasons are manifold, with the first and most critical being the way football pummels the brains of its players. It feels ethically dubious to embrace a sport that has the potential to do so much neurological damage to its participants. The extreme anecdotal horrors of players with CTE are devastating: in 2012, Jovan Belcher, a former Chiefs’ linebacker, shot and killed his girlfriend before turning the gun on himself in the parking lot of the team’s practice facility. That same year, Junior Seau, one of the greatest linebackers of his generation, shot himself in the chest. Both men were posthumously diagnosed with CTE, and while it may be a overly simplistic to tie their suicides solely to the disease, all were reportedly experiencing telltale symptoms, including impaired judgment, difficulty concentrating, and depression, in the months leading up to their deaths. A 2018 Harvard study found that individuals who’d experienced a single concussion in their life were twice as likely to die from suicide. What does that mean for players who suffer years, or even decades, of concussive and sub-concussive hits?

To the sport’s (slight) credit, it has taken steps to make the game safer (after, it should be noted, refusing to recognize the link between concussions and CTE until 2016), redesigning helmets, changing the kickoff rules to avoid nasty collisions, and being zero tolerance about leading with the head. While all of these changes are positive, it feels a bit like building an ice sculpture in a desert, because football is an inherently violent sport with head injuries woven into its DNA. As an article in The New York Times put it:

Stefan Duma, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech, runs a respected helmet lab that evaluates and rates them, and he has tracked the breadth of the technological leap. More sophisticated helmets and foams have reduced the acceleration of the head by about 50 percent, and all of the companies, he said, are engaged in research to develop new technologies. But he is not convinced that great advances remain. C.T.E. remains an ever-present danger no matter what a player wears on his head. “Not getting hit in the head at all is the best thing for you,” he said.

During my playing days, I had no qualms about lowering my noggin and ramming into an opponent at full speed. It was the late 90s and early 2000s, and people were only starting to care about the potential long term effects of repetitive head blows. I remember feeling a perverse sense of pride when I’d return to the huddle with my ears ringing and my eyes starry: it made me feel tough, like some dubious ideal of a man. I wasn’t giving a second thought, or even a first thought, to how these headshots might affect me decades down the road, because I was a kid, and none of the adults around me seemed to be worrying about it, either.

There we were, a bunch of children playing pee-wee, and eventually high school ball, potentially sacrificing long-term mental health for short-term glory. Was it worth it? For many of us, sure, and I might even count myself among that crowd. Some of my most vivid and enduring high school memories were made on the gridiron: winning a state semifinal with a touchdown pass in the waning minutes, competing for a state championship at Liberty University, playing a playoff game in front of 10,000 fans…all of these moments have been seared into my memory like the NFL logo on the side of a pigskin. But will I continue to think it was worth it if, in 10 or 20 years, or even tomorrow, I start having substantial memory issues and/or violent thoughts towards myself or my family? This troubling future may never come to pass, of course; maybe, hopefully, I’ll be fine. Plenty of former football players go on to lead normal lives. But the possibility is always lurking in the shadows, a dark seed potentially planted in youth waiting for the right conditions to split my mind wide open.

I remember feeling a perverse sense of pride when I’d return to the huddle with my ears ringing and my eyes starry: it made me feel tough, like some dubious ideal of a man. I wasn’t giving a second thought, or even a first thought, to how these headshots might affect me decades down the road, because I was a kid, and none of the adults around me seemed to be worrying about it, either.

Even if the seed doesn’t germinate within me, it already has in others. I recently had a conversation with a fellow pre-K dad while watching our young sons break pieces of wood at taekwondo. We were talking about sports, because men, and somehow the conversation turned to whether we’d allow our sons to play football. He scrunched up his face as if it was a painful question: he’d played in college, and his dad had been on the team at Syracuse, so he reasoned his son would probably be a good player, too; it was, after all, in his blood. Yet he couldn’t seem to convince himself that it was worth it: he talked about how a surprising number of his dad’s teammates had become riddled with cognitive issues like dementia and Alzheimer’s. He was worried that he himself might even be experiencing some symptoms of CTE from all those years of concussive and sub-concussive hits, and since he’s older than me, concussion protocol was even less stringent during his playing days. If you got your bell rung, a perhaps dated slang term for a concussion, you sat out for a few plays, maybe a couple drives, then jumped right back into the melee. This is especially dangerous, of course, because the only thing worse than a concussion is another concussion (second impact syndrome, as it were). Who knows how many head injuries he incurred? Who knows how the pounding his brain took during his playing days will affect him as he continues to grow older?

There are other, less-grave reasons why I’ve fallen out of love with football; these are more a matter of personal preference than greater concern for player safety. I fear that, in the following paragraphs, I may start to sound like an old man yelling at the clouds. If so, then very well, I’ll jump right into the first of my old man gripes: the way football has become such a watered down extension of consumerist culture that I can’t help but find it frustratingly bland, like another McDonald’s sign erected along a chain-clogged American highway. The clunky maximalization of commercial breaks alone is enough to give one pause: I think we’ve all had enough of Patrick Mahomes, Travis Kelce, and/or Peyton Manning trying to sell us stuff, or FanDuel urging us to bet on everything all of the time. This approach of jamming as many advertisements as possible into a broadcast, coupled with the implementation of replay challenges, has made a televised NFL game a very bloated thing, indeed: the average length of a game is now three hours and 12 minutes, which, by the way, is more than 30 minutes longer than the average MLB game, a sport that was hobbled by pace-of-play complaints for years before implementing some clever rules that have sped things up. Baseball also has two-minute breaks between half-innings where it feels natural to slip in commercials, but football doesn’t, which makes its advertising timeouts feel awkward and disjointed, or as a New York Times article put it:

Television commercial breaks are the bane of every N.F.L. fan. They interrupt a game already riddled with stoppages, bombard viewers with come-ons and force fans and players in the stadium to stand around for about two and a half minutes, sometimes in the freezing cold.

A game already riddled with stoppages, indeed: it’s not just the absurd amount of advertising that makes watching football games laborious, it’s the fact that there’s not all that much action to begin with. A now semi-famous study by The Wall Street Journal found that there’s only about 11 minutes of play in the average NFL game, a total surpassed by time spent on replays (17 minutes), dwarfed by time spent watching players stand around (67 minutes) and, of course, weaved through a soul-crushing tapestry of ads (45-60 minutes). What this amounts to, from one perspective, is a whole lot of hype for very little substance: talking heads like Stephen A. Smith shouting like over-caffeinated maniacs all week, ceaseless overreactions and predictions from “experts,” the hours upon hours of pregame shows…all of it culminates in a game that offers only 11 minutes of action. In all fairness, this data point could be seen as deceptive, considering there are often genuinely riveting moments packed into those 11 minutes, but it does make you wonder: what are we actually watching when we watch a football game?

There was a time not all that long ago, even after I’d fallen out of love with the NFL, when I could get carried away by a good old-fashioned college football game. I still can, to an extent, though it seems to happen less frequently with each passing year. Contemporary college football hardly resembles the game I grew up with, what with the transfer portal and the N.I.L. and the wackadoodle conference alignments (Stanford in the ACC, I mean, come on). Back in my day, a player could have a Heisman trophy stripped from him for procuring rent-free housing for his parents, and a program actually had to be located on the East Coast if it wanted to play in the ACC. This isn’t a moral judgment, per se, just a statement of fact, though I’m obviously a little bit salty about it. (See? Old man yelling at the clouds).

There are two schools of thought around the cataclysmic changes that have reshaped the college game: (1) that they’re necessary correctives for student-athletes who’d been taken advantage of by money-gobbling schools for decades, and (2) that they’re going to turn the sport into something grotesque and indecent. These lines of thinking are not mutually exclusive; indeed, I consider myself an adherent of both: yes, players absolutely should be able to make money off their image and likeness, and also yes, this sea change has the potential to disfigure the sport beyond recognition. In fact, it has already begun to do so. The New Yorker recently ran a piece about Bill Belichick’s new gig as head coach at UNC, which touched on the prevailing ambivalence about the new rule changes. The writer, Paige Williams, went to a bar in Chapel Hill to get a sense of how the common folk were feeling about it all:

Chip Hoppin, a fifty-year-old screen-printer who was drinking Guinness, whirled around on his barstool and said that he strongly supported paying student athletes but that money was “ruining all of sports, honestly.” He said, “Would you pay any seventeen- or eighteen-year-old to do anything—carpentry, play an instrument at your wedding—before the job’s done? No!” He preferred an incentive model: win a conference or a national championship, here’s a bonus. College football had become a free-for-all because of “rich old white guys with so much money they don’t give a fuck about anything.”

Contemporary college football looks more like the NFL every time I watch a game, which is a very meh thing, indeed. I recently read an article in Sports Illustrated about how Arch Manning, Texas’ starting quarterback, heir to the Manning quarterbacking throne, and the highest-valued collegiate athlete in the country, has no desire for fame and attention. “Arch would prefer never to be in the paper or take a picture or do a commercial, or do anything that would require attention on him,” said his dad, Cooper. Later that day, during the Ohio State/Texas snoozer of a game, I witnessed back-to-back Warby Parker commercials featuring a bespectacled Arch beside his likewise bespectacled father. I can’t blame the kid for wanting to make a buck; he is a Manning, after all, and I’d be doing the same thing if I was in his shoes. But it had a tang of disingenuousness to it, and was also a blunt reminder of how the new rules have redrawn the contours of acceptability in the college game. Later on in The New Yorker article, Williams describes how the new rules have turned Division I college towns into hedonistic bacchanals that would’ve been unconscionable in the recent past:

This spring, the Times declared U.N.C. to be “at the forefront of the next stage of the N.I.L. era.” Carolina has more than eight hundred student athletes, and Article 41, a self-described “talent management and social training” firm, was trying to turn all of them into influencers. Vickie Segar, a founder of the company, said that U.N.C. wants “every athlete at the school to make as much money as possible because it will get better athletes.” In Chapel Hill, I heard people talking about athletes who drove brand-new vehicles, acquired from local dealers in exchange for social-media posts. Restaurants name dishes after players and let them eat for free…At Chapel Hill Sportswear, on Franklin Street, Holly Dedmond, the store’s longtime manager, showed me racks of unsalable N.I.L. merchandise tied to players who’d wound up transferring.

We’re living through an era in college football in which the soil underfoot is shifting in fundamental and perhaps irreversible ways. Only through the lens of history will we begin to understand if these changes were the beginning of the downfall or merely a new chapter in the sport’s long and successful history. Given the fervor with which fans have long devoted themselves to the college game, it seems unlikely that the rule changes will have any long-term negative impacts. College football, after all, is closer to religion than sport for many people. This includes author Tommy Tomlinson, who penned a brief but fantastic essay in Garden and Gun that captures the religiosity of big-time college football:

College football rewards those who believe. A lot of it, on and off the field, resembles the Old Testament—nasty and brutish and tedious. But you live through the Old to get to the New. And one Saturday night, late in the game, your man breaks into the clear. You rise and shout. Rapture.

This sense of holiness in the college game makes it feel existentially important to millions of people, and it’s an instinct I empathize with. The fact that each team only plays one game per week, only half of which are at home, coupled with time-honored traditions like tailgating and band-led fight songs, make each one feel like a hallowed communal event, not unlike going to church on Sunday. Like religion, college football offers a sense of social and spiritual fulfillment, but when taken to the extreme, it can lead to a blind devotion that breeds myopicness. The older I get, the more I want sports to have a sense of perspective, or at the very least a sense of humor, which I guess in its own way, is perspective. Mostly I don’t want a sporting event to feel like religious or political warfare, I want it to feel like the children’s game that it is at core.

Perhaps this is why I’ve gravitated back to baseball in my mid-30s while simultaneously drifting away from football. Viewing the two sports in a live setting is a study in two distinct, and frankly opposite, life philosophies: going to a baseball game usually means enjoying a nice, lazy summer day (or night) outside with your friends and family, chatting about life while drinking a beer and eating a pretzel, occasionally turning your attention to the action when a player makes a diving catch or hits a home run. Attending a football game is akin to snorting cocaine and being thrust into the pit at a Slipknot show: people are decked out in war paint and hollering at each other, it’s loud as hell, your nervous system stays in fight-or-flight mode for most of the game, and there’s a 63-percent chance you’ll end up in a verbal or physical altercation (note: not an actual stat). The animalistic nature of football has captivated the American imagination for decades, and there’s no denying that attending a big-time college football game can feel like a step into a world of feral divinity. Again, here’s Tomlinson:

I have touched the divine in Athens on a Saturday night. I have been baptized in Jim Beam and Coke after a kick went through the uprights at the final gun. I have seen the face of God at the old Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, the day my alma mater, Georgia, beat Florida when Florida was No. 1 in the country. Thousands of fans ran down onto the field, and all of a sudden there was the Lord, kneeling beside me as we dug up chunks of turf. We headbutted each other, then hugged.

I get where Tomlinson is coming from. In 2018, I went to an Ohio State/Penn State game in Happy Valley with my dad and brother. Both teams were ranked in the top 10. It was a nationally-televised game, and also a “White Out” night, meaning nearly all 106,000ish fans were wearing white shirts and going absolutely bananas for the better part of three hours under the bright lights of Beaver Stadium. It was, hands down, the most electric atmosphere I’ve ever experienced. There was one Ohio State fan in our section, and when it became clear the Buckeyes were going to win, he got cocky, drawing the ire of the Penn State fans surrounding him. The animosity escalated to the point of some light shoving, causing my dad, brother, and I to lob curse words at him like we were preparing to pummel him in a Pittsburgh alley. It was tribal, it was ridiculous, and on some level, kind of awesome. In what other setting is such unhinged behavior even remotely acceptable? It can feel exhilarating to embrace our primal nature for a few hours, to shed the masks of our put-together public selves and step into the jungle, as it were, to act like maniacs while watching something akin to Roman bloodsport.

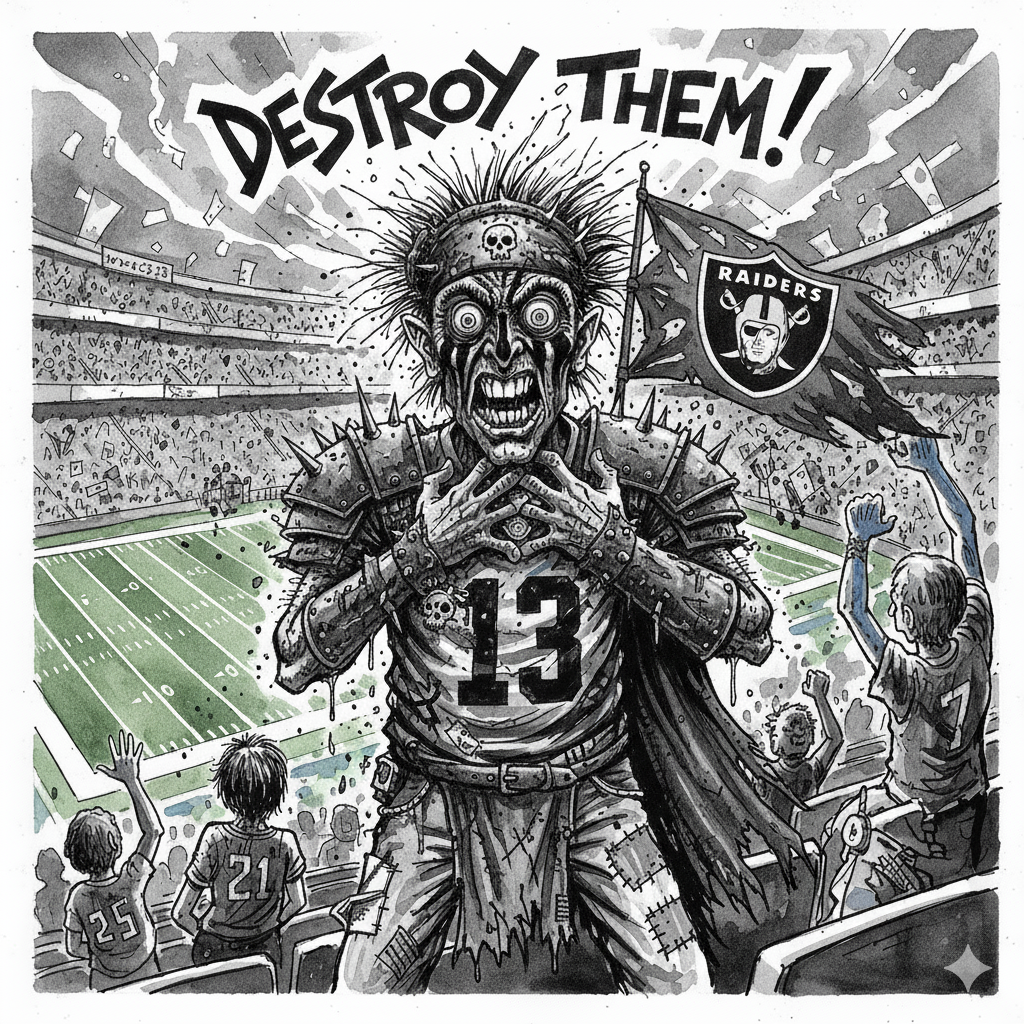

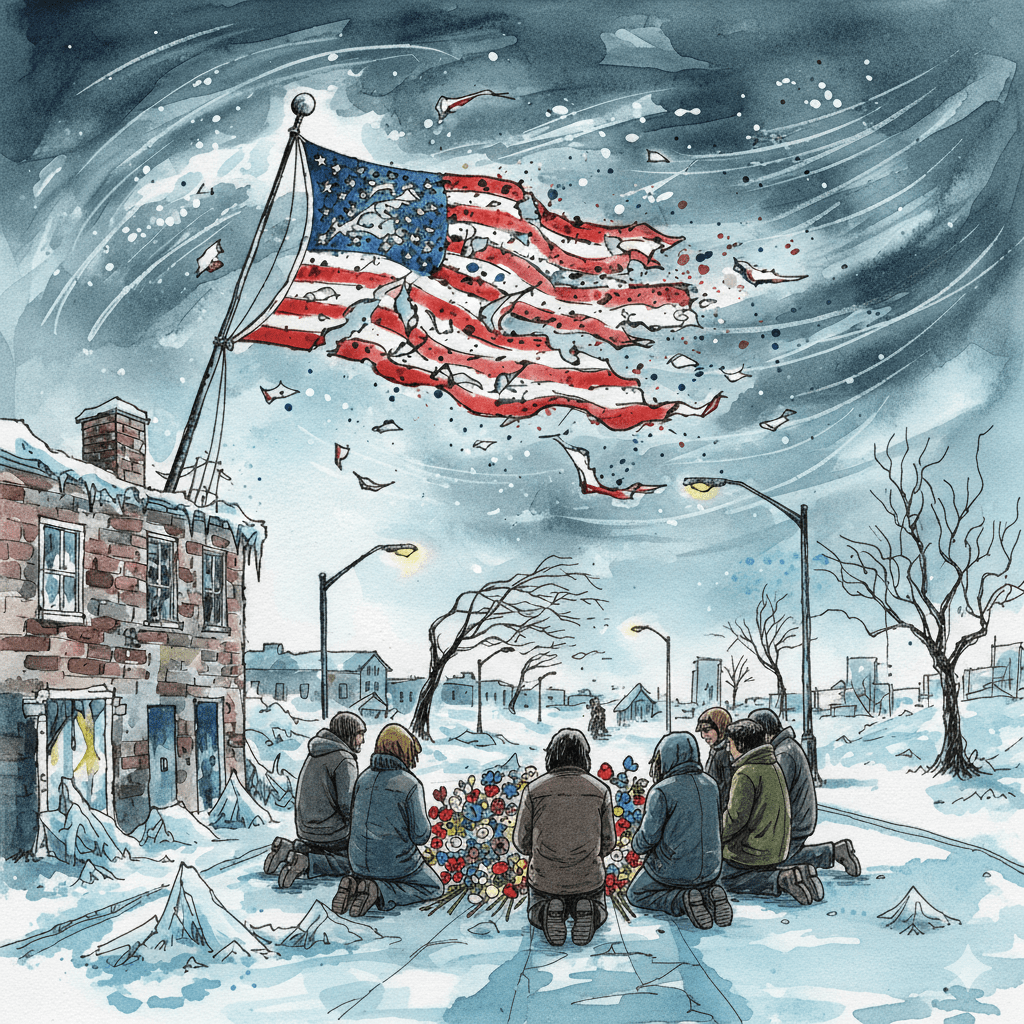

When competition is framed like this, as a war, it makes sense to view the guys on the other side, whose humanity is obscured by facemasks and armor, as fundamentally bad. If a war is on, then the stakes are life or death, and the only sensible way to compete is through a gut-level instinct for survival, and the best means for ensuring survival is by annihilating the Other.

That’s the rub, though: I’ve never liked the ravenous side of me that comes out when I’m invested in a football game. The dominant emotions I remember feeling during high school games, to the extent I remember them at all, were fear and rage, with occasional moments of profound sorrow and brilliant ecstasy sprinkled in. Off the field, I was mostly mild-mannered and agreeable, but as soon as I donned a helmet, I transformed into a fire-eyed lunatic driven not by intellect or empathy, but raw emotion. I once whacked a teammate, our right guard, in the back of the helmet as hard as I could for committing the unabsolvable sin of jumping offside. I routinely cursed at players on the other team and got into scuffles. I, like many of my teammates, went insane for a couple of hours; we weren’t players in a game, after all, but soldiers in a war, to steal a metaphor often deployed by football coaches at every level. When competition is framed like this, as a war, it makes sense to view the guys on the other side, whose humanity is obscured by facemasks and armor, as fundamentally bad. If a war is on, then the stakes are life or death, and the only sensible way to compete is through a gut-level instinct for survival, and the best means for ensuring survival is by annihilating the Other. This framing gives football its hyperbolic sense of importance, its feeling of urgentness, but what lessons is it teaching? One of our pregame rituals in high school was huddling around an assistant coach while he called out players on the other team, number-by-number, to which we’d respond: “fuck ‘em up!” Compare this to the rituals practiced by my high school baseball team: bleaching our hair before the playoffs, playing Mario Kart 64 while sitting in folding chairs, watching our center fielder juggle baseballs while walking around the perimeter of the field, and dancing to “Apache (Jump on It)” in the locker room after big wins. Which of these cultures seems more life-affirming?

I can’t help but feel that football is a game that’s often played and watched with a sense of malice, or at least aggression, in one’s heart… a constant desire to fuck up the opponent by any means necessary. In this sense it doesn’t feel like a very human game: the players on the field seem less like actual people and more like robot warriors programmed to seek-and-destroy. I’m sure many people would disagree with this assessment, perhaps claiming that it’s passion, not malice, they feel while watching a game. Who am I to say they’re wrong? People are allowed to love football for their own personal reasons, and I’m sure there are many football-loving writers out there who could pen some very convincing words about why my characterization of the sport is misguided. Maybe they’d even change my mind about some things.

As it stands, though, I’ll end with an example of the kind of love and warmth I see in baseball that, to me, is often lacking in football. Earlier this month, Anthony Rizzo, one of the biggest stars of the 2016 Chicago Cubs team that won the franchise’s first World Series in over 100 years, returned to Wrigley Field to retire with the team. He spent the bulk of the game in the left field stands, hanging out with the Bleacher Bums, as they’re called, laughing and joking and, at one point, rallying fans to build a plastic beer cup snake that extended back at least five rows. At another point in the game, Cubs’ rookie Moises Ballesteros hit his first major league homer directly to Rizzo (what are the chances?), who promptly dropped the ball. The fans around him went crazy with laughter and jubilation at the improbability of any ball at all being hit to him, and the irony of a former big leaguer failing to make the catch. These are the moments of light-heartedness I like to see at sporting events, and it feels like I don’t see them very often at football games, though I’ll admit, I’m not watching very much anymore.

Football, on the other hand, feels like an impassioned fling that reached orgasmic highs but was ultimately unsustainable, mostly because it asks a hell of a lot out of me: to accept the way games are billed as para-military conflicts, to endure unrealistic hype, to be patient during consistently jarring commercial breaks, and, most demanding of all, to ignore the serious ethical questions around the long-term health of its players.

It may feel discordant to end an article about football with a perhaps romanticized scene from a baseball game, but I think it gets to the heart of my divorce from football. Baseball, although it has a dark side (the Steroid Era, gambling issues, obscenely inflated salaries, etc), has grown into a healthy lifelong relationship for me because it doesn’t ask too much: I can turn on a Cubs game virtually every day during the summer and passively absorb it while I’m doing chores around the house. If they win, great, if they don’t, it won’t bother me for more than a couple of minutes. Football, on the other hand, feels like an impassioned fling that reached orgasmic highs but was ultimately unsustainable, mostly because it asks a hell of a lot out of me: to accept the way games are billed as para-military conflicts, to endure unrealistic hype, to be patient during consistently jarring commercial breaks, and, most demanding of all, to ignore the serious ethical questions around the long-term health of its players. The more time football and I spent together, the clearer it became that our worldviews did not align, that we weren’t clicking like we used to, that things weren’t going to work out. This is completely fine, of course: really, it is, because most of us shouldn’t marry the person we most lusted after in middle school, anyway.

Leave a comment