Note: This piece was written in October 2024, a month before the election, so keep that in mind while reading.

I: Revisiting Hillbilly Elegy

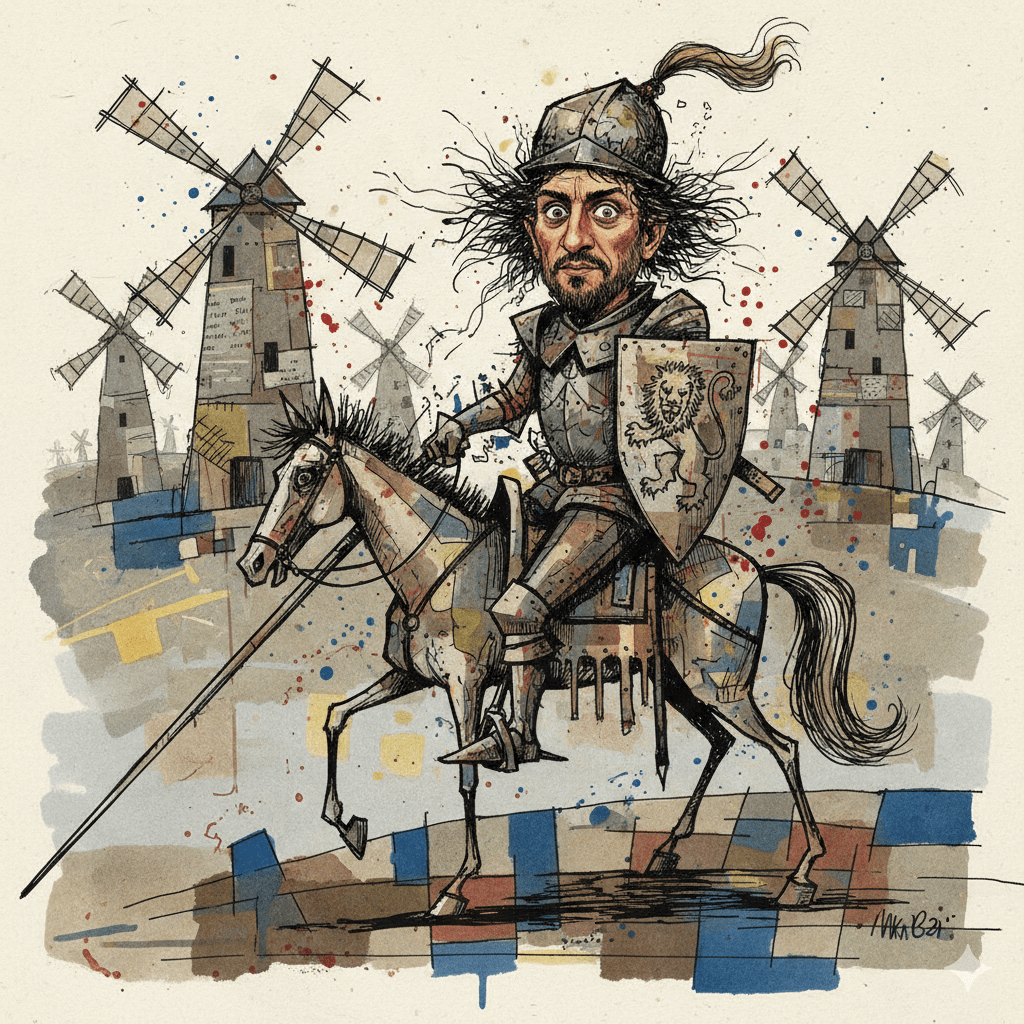

I don’t know how to feel about J.D Vance. Maybe I should by now, but I don’t. Maybe a lot of you have already made up your mind about the guy, and if so, that’s great. Maybe your political sensibilities are more astute, your sense of morality more keenly developed. All I’m saying is I can’t bring myself to fully embrace or renounce the guy, despite how convenient it’d be to do either. I’m fascinated by the warmth he portrays in long-form interviews, yet off-put by the mutability of his personality, which leads me to distrust even his most seemingly sincere motives. It’s no surprise, then, that I’m equally torn about a book he wrote eight years ago. It’s called Hillbilly Elegy. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Elegy made Vance a regular presence on national media outlets and planted the seed for his improbable political ascension. At core, it’s a memoir about his tumultuous upbringing in Middletown, Ohio, by his foul-mouthed, wise grandma (Mamaw), his gruff, soft-hearted grandpa (Papaw) and his intelligent, drug-addicted mother. Some critics of the book have pointed out that Middletown isn’t technically Appalachia (it’s right on the cusp), and argue that this fact makes the whole enterprise illegitimate. I don’t prescribe to this wholesale disregard of Elegy, at least on that front, because the truth is more nuanced: Vance’s grandparents were from Jackson, Kentucky, which is as Appalachian as it gets, and Vance apparently spent a lot of time there during childhood summers. Vance himself may not be a child of Appalachia, but he is a grandchild of Appalachia, and certainly a child of the Rust Belt, which is Appalachian adjacent and shares many characteristics with the mountainous region.

The book grew into a sensation upon its release, becoming a New York Times bestseller and turning Vance, rightly or wrongly, into a de facto spokesperson for the plight of the Appalachian working class. He became the left’s favorite conservative, because of, among other things, his vocal anti-Trump stance and multi-racial family (his wife, Usha, is the daughter of Indian immigrants). I didn’t read the book when it first came out, because frankly I wasn’t paying all that much attention, but since Vance will be our vice president next month, I figured it was my duty as a citizen and a book-lover to give it a go. I checked out the audiobook from the Staunton library (physical copies of the thing were on hold until infinity) and over the course of a couple weeks, listened to Vance recite his story in half-hour chunks during my morning commute, cringing every time he said “APP-uh-LAY-shuh,” the northern pronunciation, instead of “APP-uh-LATCH-uh,” the southern pronunciation. It’s like my wife, who grew up in Roanoke, often says: “I’ll throw an apple at’cha if you don’t say APP-uh-LATCH-uh.”

Regional dialects aside, I went into the listening experience wanting to tear the thing to shreds. I’d read many critiques of Elegy beforehand, including two full books dedicated to explaining why it is mostly an inaccurate, or at least incomplete, representation of the Appalachian region. Most of those criticisms are sound, but I think reading them prior to diving into Elegy was a mistake, because it led me to assume that Vance’s book would be devoid of redeeming qualities. This isn’t true: Elegy, for its many faults, is a worthwhile read, and it undoubtedly succeeds as a memoir. It wouldn’t have sold so many copies and been made into a major motion picture if it wasn’t, at the very least, entertaining, and it’s impossible not to be intrigued by the colorful cast of deeply-flawed characters (aka Vance’s family members) that the author presents to us, including his Mamaw, who once set her husband, Papaw, on fire after he came home drunk, and Vance’s troubled mother, who among a seemingly infinite number of misgivings, threatened to commit vehicular suicide with a 12-year-old Vance in the car. If these stories are true, and we have no reason to believe they aren’t, considering Vance published them for his entire family to read, it’s hard not to pity the guy for the childhood trauma he endured. What most surprised me while listening to Elegy was how much sympathy I felt for him, and truth be told, how much I liked him. In his best moments he comes across as thoughtful, humble, articulate and self-deprecating. When he’s in a certain mood, Vance possesses a gift for reason and pathos that stands in stark contrast to the Trumpian default of narcissistic vitriol. It’s no wonder liberal news outlets embraced him.

Elegy works as a memoir because Vance is an engaging (not exceptional, but engaging) writer, and his story is genuinely interesting: here’s a guy who grew up embroiled in family chaos, who was raised in a part of the country (technically Appalachia or not) where, as he points out, few people ascend to the stratosphere of the Ivy leagues. Yet that’s exactly what he did: he attended Yale Law school and went on to enjoy significant socioeconomic success in the meritocratic world beyond working class Ohio. His rise to the upper class wasn’t seamless, as evidenced by the many anecdotes he tells about his awkwardness in the presence of high society, including one about attending a networking event in college where he ordered sparkling water not knowing what it was, then proceeded to spit it out once he realized it was simply unflavored, carbonated water. I can’t vouch for Vance’s motivations for telling these stories, but taken at face value, they’re compulsively readable, and they portray a man who could be considered an embodiment of the American Dream, which is probably the exact reaction he was trying to elicit.

II: What He’s Getting Wrong About Appalachia

There are two places where Elegy loses me, and both of them stem from Vance’s attempts to push the book beyond its memoir wheelhouse and into the realm of cultural criticism. One of the main hang-ups I have with Elegy is Vance’s tendency to soft-pedal the role opportunistic industrial companies played in creating and perpetuating working class strife in Appalachia and the Rust Belt. Vance doesn’t deny that both regions have had their once-stable blue collar careers widely hollowed out, that industry often exploited the land and its people then skipped town. In fact, he admits he once accepted this as an explanation. Yet he continuously downplays its significance, opting instead to prescribe hard work and personal responsibility to the myriad problems industry barons had a significant role in causing. As he puts it: “These problems were not created by corporations or governments or anyone else. We created them, and only we can fix them.” If Vance’s aim with this quote is to empower the working class, then fair enough, but for him to claim everyday people were the prime movers of these issues shows he’s either operating in bad faith or is blind to historical fact. Take the following words from John O’Brien’s 2001 memoir At Home in the Heart of Appalachia, which explores the origins of industrial exploitation in the region:

In the 1870s, a serious recession dried up venture capital in America, but when the recession ended within the decade, it was as if a dam had burst. Thousands of ruthless, thoroughly dishonest agents swarmed into the mountains…Appalachian families were cheated, threatened, bullied and swindled out of ancestral land. Coal and timber boomtowns exploded into existence. By all accounts there were open sewers where brutal beatings, murder, drug addiction, alcoholism, disease, malnutrition, medieval living conditions, insanely unsafe working conditions, and environmental rape were everyday occurrences. In the Appalachian Mountains, the golden age of laissez-faire capitalism was one of America’s greatest nightmares. Within forty years, timber companies had clear-cut the oldest and largest hardwood forest that human beings would ever see. In that time, thirty billion board feet of quality lumber and an equal amount of pulpwood left the state, along with 98-percent of the profit. This was enough wood to build a thirteen-foot wide, two-inch-thick walkway to the moon. The figures from Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee are comparable. Both coal and timber operations ravaged enormous portions of the mountain landscape as well as subsistence cultures that had survived peacefully for more than 100 years. All of this transpired while county officials and local newspaper editors – who often became coal or timber executives – looked the other way.

Further to this point, here’s a passage from What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, which paints a picture of just how ruthless coal companies could be toward native Appalachians:

Testifying against coal companies in eastern Kentucky, young women described watching bulldozers rip through a family cemetery. Alice Sloan, a Kentucky-area educator, described how Bige Richie pleaded with the coal company to spare the grave of her child: “the bulldozer pushed over the hill and she begged them not to go through the graveyard. And she looked out there and there was her baby’s coffin come rolling down the hill. One man said he wouldn’t go through and push it down. The other said, ‘Hell, I will,’ and he took the bulldozer and went right on through.”

I think Vance’s argument against blaming industry for present-day problems would go something like “people need to stop blaming the past and focus on what can be done now to improve their lives.” There’s a modicum of truth in that logic, but it fails to tell the whole story. I’m not anti-hard work and responsibility, and I absolutely believe that some personal problems can be made better by taking ownership of one’s life. I also have little doubt that many folks, not just Appalachians, could benefit from a sense of initiative and empowerment. Yet to pin the blame entirely on the individual and absolve the industrial and pharmaceutical companies of guilt is naive at best and malicious at worst. Vance fails to strike a balance between the two viewpoints: an acceptance that, yes, the corrosive boom/bust nature of industry has made, and to a large extent still makes, life difficult for many people in Appalachia, and that pharmaceutical companies pushed prescription opioids for profit and fueled an addiction crisis in a vulnerable population, and because both of these things are true, there also needs to be pragmatic government intervention and, as Vance prescribes, a reckoning at the personal level about what can be done to improve individual circumstances. Vance is right to posit that dwelling on a dark past does little good, but he’s wrong to think that ignoring the ways in which that past created problems that are still being dealt with today is the way forward.

I don’t know what, exactly, a good path forward looks like, though government initiatives like President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act seem like a good start. I also know that hard work can only take certain people so far. For instance: it doesn’t matter how hard a single mother of three works at her low-wage job at the Dollar General, it’ll be extremely difficult for her to to pull herself out of poverty, especially if she wasn’t blessed with a supportive extended family like Vance. Between working long hours and taking care of her children, when does she have the time or the money to, for instance, take classes at a local community college, especially considering she lives in a country where childcare, healthcare and higher education are uncommonly expensive? For her, the American Dream may seem like a farce, or something akin to a slap in the face. Just because Vance was able to rise up and out of Appalachia doesn’t mean that everyone who grew up in similar circumstances has the means, time, intelligence, stamina, or support system to do the same. And besides, not everyone wants to leave Appalachia. It’s a warm and welcoming home to many people, a beautiful place brimming with a sense of spirituality.

The second problem I have with Elegy is kind of a two-parter: Vance’s disproportionate focus on the negative aspects of Appalachia, and the way he implies that his turbulent upbringing is, if not the regional norm, something close to it. The subtitle of Elegy is “Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis,” but perhaps it would’ve been more accurate to omit the word “culture,” because the trauma he experienced as a child is the furthest thing from a communal norm. How many people have been forced to testify in court against their mother because of physical abuse? How many had a grandmother who doused her husband in gasoline and lit him on fire? How many had an uncle who beat someone unconscious and cut him up with an electric saw? Another uncle who forced someone to eat panties at knife point? These are Vance’s stories to tell, and I have no issue with him recounting them within the context of a memoir, but to project these extreme personal experiences as somehow emblematic of a region writ large is grossly misrepresentative and willfully sensational.

Dwight Billings, in his essay titled Once Upon a Time in ‘Trumpalachia,’ tells students in his Appalachian studies courses to “beware two intellectual tendencies in writings about any group – essentialism (‘this is the essence of what they are like’) and universalism (‘everyone in the group is like this’). Vance heaps on both.” Consider the following quote from Elegy, which drives to the heart of Vance’s feelings about the working class, and operates as a nexus upon which the rest of the book turns:

Our homes are a chaotic mess. We scream and yell at each other like we’re spectators at a football game. At least one member of the family uses drugs – sometimes the father, sometimes the mother, sometimes both. At especially stressful times, we’ll hit and punch each other, all in front of the rest of the family, including young children; much of the time, the neighbors hear what’s happening. A bad day is when the neighbors call the police to stop the drama. Our kids go to foster care but never stay for long. We apologize to our kids. The kids believe we’re really sorry, and we are. But then we act just as mean a few days later.

We choose not to work when we should be looking for jobs. Sometimes we’ll get a job, but it won’t last. We’ll get fired for tardiness, or for stealing merchandise and selling it on eBay, or for having a customer complain about the smell of alcohol on our breath, or for taking five thirty-minute restroom breaks per shift. We talk about the value of hard work but tell ourselves that the reason we’re not working is some perceived unfairness: Obama shut down the coal mines, or all the jobs went to the Chinese. These are the lies we tell ourselves to solve the cognitive dissonance – the broken connection between the world we see and the values we preach.

Vance goes on like this for several paragraphs, but I think you get the idea. His use of the word “we” and “us” makes it seem as though these experiences are standard realities, which, of course, they aren’t. There are kernels of truth in the above passage, families for whom Vance’s words may ring true. To his (slight) credit, he does mention, in the paragraph after his questionable rant, that “not all of the white working class struggles” and proceeds to differentiate between the mores of his grandparents (“old-fashioned, quietly faithful, self-reliant and hard-working”) and those of his mother and, as he puts it, “increasingly, the entire neighborhood” (“consumerist, isolated, angry, distrustful”). The problem with Vance’s words are that they lack proportion and tend to omit the positive. It calls to mind what Trump said about illegal immigrants: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. Some, I assume, are good people.” Stable families are as rare in Vance’s Appalachia as virtuous illegal immigrants are in Trump’s America. Likewise healthy relationships, and, it would seem, decent human beings. Vance offers few counterpoints to his gloomy vision of Appalachia, and thus paints the whole region as a place with scant redeeming characteristics, a place that mostly exists to be escaped from.

Stable families are as rare in Vance’s Appalachia as virtuous illegal immigrants are in Trump’s America. Likewise healthy relationships, and, it would seem, decent human beings. Vance offers few counterpoints to his gloomy vision of Appalachia, and thus paints the whole region as a place with scant redeeming characteristics, a place that mostly exists to be escaped from.

In focusing on this idea of Appalachians as a inherently-flawed people, Vance plays into negative stereotypes that have plagued the region for more than a century, stereotypes that were exploited and to a certain extent created by big wigs of industry who benefited immensely from the image of the anachronistic hillbilly prime for capitalist salvation. Appalachians needed to be guided into the 20th century, so the story went, and corporations would be their shepherd. Here’s another passage from What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia:

Late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Social Darwinism posited that wealth and privilege fell naturally to those who most deserved them and that social differences between the rich and the poor reflected differences in their innate abilities…The poor might improve their station through hard work and industry, but those of greater means owed them nothing in this struggle. This theory befit a world enthralled by the free market and the competitive accumulation of capital. Many industrialists felt little responsibility to their workforce, often believing that their social assistance would encourage an undesirable overpopulation of the lower classes.

Coal companies often justified their expansion and the recruitment of local populations into their workforce as benevolent actions that would bring backward mountaineers into their own as equal participants in America’s expanding spirit of industry…A desire to “tame” Appalachians for the benefit of industry often lurked behind twentieth-century theories of Appalachian otherness…if you trace a flawed narrative about Appalachia back far enough, you’ll often find someone making a profit.

O’Brien, in his aforementioned memoir, wrote about how pervasive these flawed narratives about “hillbillies” had become during his cross-country travels. No matter where he went, he seemed to encounter people who thought of Appalachians as strange and violent others, a perception that didn’t jibe with his personal experience in the region:

They knew all about Appalachia – strange, backward people struggling with grinding poverty in a devastated landscape; feral hillbillies; Hatfield’s and McCoys, black-bearded moonshiners murdering one another…occasionally there was just enough truth to some of these misconceptions to make them understandable. I knew about hard times in the coalfields, but thought all of that had to do with American industry and exploitation rather than hillbillies. I had at least heard about the Hatfield and McCoy blood feud, and while mindless violence had nothing to do with any West Virginian I’d ever met, I assumed there was some truth to the story. But it was as if Becky [his wife] and I had said we were from Texas and then people began to talk about gunfighters, cattle drives, “injun” trouble and ruthless oil barons. At times trying to explain was pointless. People had read things about Appalachia or seen things on television and they knew.

Positive stories about non-caricatured people are mostly non-existent in Elegy. It’s not that Vance lacks kind words about his relatives: he waxes poetic in several passages about the merits of his Mamaw, Papaw, sister and even his mother (who is now a decade sober), and genuinely seems to love all of them. It’s the fact that he conveys these virtuous characteristics as exceptions and assumes the natural state of the average “hill person,” as it were, is anger and violence. Vance’s use of the word “elegy” in the title is perhaps telling, too: an elegy, of course, is an expression of grief for the dead. So what is the title insinuating? That hillbillies, that vague, misrepresented subgroup of people, have already died and are in need of mourning? Or that hillbillies, in the abstract sense in which Vance views them, need to die, so that the next generation of mountain people may transcend their “troubled” past and rise to greater socioeconomic heights? Vance’s motivations behind the title are unclear, but if I had to guess, I’d say it amounted to little more than the fact that it had a brisk, sensationalist ring that would help sell books.

Or perhaps that’s an overly-cynical take. Maybe Vance came to the title earnestly. Maybe the “elegy” he speaks of is a genuine expression of grief for his late Mamaw and Papaw. Perhaps Vance wrote the book in their honor to express the gratitude he feels for their willingness to instill within him the values of self-reliance and hard-work, values that he believes allowed him to rise above the din of family dysfunction, get the hell out of Middletown, join the Marines, graduate from Yale law, make tons of money as a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and become the Vice President-elect of the United States.

III: The Mutability of J.D. Vance, Sound Bite-Centric Media, and Springfield’s Illusive Pet-Eating Migrants

A lot has changed in the eight years since Vance published Elegy, Vance included, who has morphed into something physically and ideologically unrecognizable from the 2016 version of himself. He’s lost 30 pounds and grown a beard that serves him well. Once pudgy and baby-faced, he’s now trim and serious. He’s abandoned his hardline anti-Trump stance, a phase in his life that saw him call the current President-elect, among other derogatory things, “cultural heroin,” a “moral disaster,” a “total fraud,” and “reprehensible.” He’s embraced election denialism, refusing to admit on several occasions that Trump lost in 2020, despite numerous court cases refuting such assertions. When asked by The New York Times about his seemingly radical change of heart, Vance explained it thus: “What I slowly learned is that if you believe that the American political culture is fundamentally healthy but maybe biased toward the left, then Donald Trump is not the right solution. If, as I slowly developed the viewpoint, that the American political culture is deeply diseased and the American political conversation had become so deranged that it couldn’t even process the frustrations of a large share…of the country, then when you say ‘I don’t like Donald Trump’s language,’ well, Donald Trump’s language makes a whole lot more sense if you assume the institutions are much more corrupt than they were before. The point that I got to was, if Donald Trump didn’t talk like this, and if he wasn’t going directly at the institutions, then he wouldn’t be able…to illustrate how broken the American political and media culture is right now. What I saw in 2016 as a fault of Donald Trump’s, by 2018 and 2019 I very much saw as an advantage.” There’s a lot to push back on there, but for the sake of time, let’s leave it alone. Vance is allowed to change his opinion on things. Politicians on both sides of the aisle do it all the time. It does seem curious, however, that he changed his tune on Trump around the same time he became more politically ambitious.

I can’t pretend to know Vance’s heart. All I can offer is an outside perspective from evidence he’s presented in Elegy and in public appearances. Early on in Elegy, he writes about the procession of father figures his mother brought into his life, and how he would shape-shift to win their favor, an understandable means of self-preservation for a confused kid pining for acceptance. When his mom brought home Steve, a guy Vance called “a mid-life crisis sufferer with an earring to prove it,” Vance started wearing an earring. When his mom’s next boyfriend, a cop named Chip, thought earrings were feminine, Vance acted like he had “thick skin and loved police cars.” He also employed this mutability of identity when his biological father, a snake-handling holy-roller, re-entered his life: Vance absorbed the tenets of new world creationism, and started seeing signs of the devil in everything from rock music to evolutionary theory. It’s easy to draw a direct line from Vance’s childhood transmutations to his profound shift from self-proclaimed never-Trumper to his presidential ticket-mate: perhaps Vance saw in Trump the ultimate conditionally-loving father figure, a vastly influential man whose good side he knew he could get on if only he could remake himself in his image, if only he could bury his own instincts so deeply that he no longer believed they were his own, while simultaneously adopting his new surrogate father’s core values with the obsessive single-mindedness he’d exhibited with his previous father figures. It was a perfect match, really: Trump the all-powerful dad, Vance the acquiescing son.

Perhaps Vance saw in Trump the ultimate conditionally-loving father figure, a vastly influential man whose good side he knew he could get on if only he could remake himself in his image, if only he could bury his own instincts so deeply that he no longer believed they were his own, while simultaneously adopting his new surrogate father’s core values with the obsessive single-mindedness he’d exhibited with his previous father figures.

Or maybe that’s too conveniently true, just faux-psychological mumbo-jumbo. It’s entirely possible that Vance’s heart has truly opened to the idea that Trumpism is America’s best path forward. If so, that’s his prerogative. To this day, part of me still wants to believe that the relatively centrist, Elegy-era version of himself still exists. Though I mostly disagree with his diagnosis of America’s current problems and reject many of the contentious things he’s said (see: below), I’ve become fascinated by his personality, not only because of the dramatic political shift that’s vaulted him, remarkably so, to the de facto torch-carrier of Trumpism, but also because when I listen to him talk, even today, I often hear a guy that, despite his faults, I truly want to like, and sometimes do like. He’s intelligent, articulate and, in his best moments, exudes a sense of thoughtfulness and warmth that has been nearly non-existent in the political realm during Trump’s eight-year reign over the Republican party. Here are some things that Vance has done as a senator, and some things I’ve heard him say in interviews, that make me want to believe that he might be decent guy after all (this is not meant to be an exhaustive list, merely a sampling):

- He went against most Republicans by supporting the Affordable Connectivity Program, which “provided a monthly subsidy to low-income Americans to pay for internet service.”

- He worked with Democrats on a rail safety bill after a devastating train derailment last year in his native Ohio.

- He worked on a bill called the Youth Poisoning Protection Act aiming to ban the sale of products with a “high-concentration of sodium nitrate.”

- On advice he would give to children who have parents struggling with addiction: “Number one is if you’re a kid and you’re in an environment where there’s a lot of addiction, don’t get into a situation where…it’s you that’s struggling, too. Number two is don’t get resentful, and keep your heart as open as possible. Don’t let your parent’s addiction become something that destroys your life, too. “

- On gratitude: “The feeling of gratitude is so empowering. If you’re grateful for what you have, and…you and your wife have an argument, but you just feel grateful for her existence, that’s such a better attitude to take. Your kid does something annoying to you, and you think ‘I’m so grateful I have this beautiful baby to take care of’…the feeling of gratitude is a very powerful thing.”

- On parenthood: “You just love your kids so much. You think the sun shines out their asses. Like a living breathing CareBear…When I was 27 or 28, I had a pretty bad temper. If someone cut me off, I’d be really pissed off…I would think, oh my God, is my kid going to do something bad and I’m going to fly off the handle. Kids can be frustrating from time-to-time, but in part because my wife is so patient and part because I’m older and a little wiser [my temper hasn’t been as much of an issue]. I’ve screwed up, I’ve made mistakes as a parent, but kids are much more resilient than people give them credit for…it’s the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done.”

Yet Vance has a highly active and public dark side, an abrasive and vindictive turn of mood that he’s embraced more enthusiastically in recent years. You’ve probably heard his most recognizable quotes, the ones repeated ad infinum by the media because of their pot-stirring qualities, but if not, I’ll recount a few here: In 2021, he told Tucker Carlson that America is being run by a “bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices they’ve made so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too. It’s just a basic fact…the entire future of the Democrats is controlled by people without children.” He called Indigenous Peoples’ Day a “fake holiday created to sow division.” He said “I don’t really care what happens in Ukraine one way or another” because he’s more concerned about the fact that the leading cause of death for 18-45 year-olds is fentanyl, as if it’s impossible to care about both issues simultaneously. When asked if he would support abortions in cases of rape or incest, he said “two wrongs don’t make a right.” Perhaps most notably, he spread a dubious claim about Haitian migrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio, then justified his dissemination of the story by telling NBC News “if I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, that’s what I’m going to do.”

Let’s double-click on that quote about him “creating stories” for a second. Vance immediately clarified his words by saying: “We’re creating a story, meaning we’re creating the American media focusing on it,” which if I can attempt to translate, means he wanted to spur interest in the situation in Springfield by crafting a narrative, not necessarily by creating an outright fiction. I didn’t buy this explanation at first, but the more I watched the clip, the more I believed, perhaps against my better judgment, that he was being earnest. I also came to believe, perhaps naively, that Vance is being truthful about having received first-hand accounts from Springfield residents about migrants eating pets, which is the explanation he’s given when the media questions his sources. Where Vance ultimately loses me is his blind acceptance of these apparent first-hand accounts as fact without a shred of verifiable evidence: no police reports, no 911 calls, no videos, nothing. The lone confirmed case of a person eating a cat in Ohio involved a mentally-troubled, American-born woman, and it happened in Canton, which is 170 miles northeast of Springfield.

If Vance was acting in good faith, he would’ve researched the legitimacy of these word-of-mouth claims before repeating them on the international stage, then doubling and tripling down. Yet he’s clung to this story like a safety blanket because it neatly fits within his party’s hardline stance on illegal immigration (though, it should be noted, that most of the Haitian migrants in Springfield are there legally under the Immigration Parole Program). If he wanted to draw attention to the real issues taking place in Springfield, of which there are many, why hasn’t he used his platform to focus on, say, how to help a school system that has been overwhelmed by a mass influx of students? Why waste time on seeming untruths when the actual truth presents very real challenges? The reason seems obvious enough: the dystopian imagery of Haitians plucking pets from their neighbors’ backyards and roasting them on a spit justifies his party’s mass deportation agenda, and drives to the heart of his base’s biggest fear about migrants from “shithole countries” (Trump’s words, not mine): that they’re the dreaded other, perhaps even inhuman, not unlike the warped caricature of feral “hillbillies” amplified by coal and timber companies to justify their greedy ends. Only a savage would eat a housecat, after all.

I’ll grant that this whole bizarre pet-eating ordeal seems to confirm one of Vance’s main criticisms of mainstream media: that it has a troubling tendency to focus on sensational sound bites, sometimes out of context and without the presentation of an alternate interpretation. It’s a sin widely committed by conservative and liberal outlets alike, one I even committed myself a few paragraphs ago by recounting the questionable things Vance has said without providing the context of the entire interview. It’s an easy trap to fall into. Juicy sound bites are, despite our better angels, what we crave. We want a person we dislike to say a few dumb things during an hour-long interview so we can hold up those questionable moments like golden tableaus and say “LOOK HOW ATROCIOUS/DUMB/OFFENSIVE/ETC ETC THIS PERSON IS!” We crave these titillating snippets because they make a complicated world seem simpler, complex people more one-dimensional. Fox News can mold Kamala Harris into an inept, word-salading fool by only airing clips that make her look like an inept, word-salading fool. CNN can mold Vance into a weird, hate-fueled bigot by only airing clips that make him look like a weird, hate-fueled bigot. It’s so easily done, and the American public is so primed to accept it, often below the level of conscious thought, that we’re essentially being conditioned to hate anyone who doesn’t share our political sensibilities. It makes us feel, on a gut level, that the other side is inherently evil, perhaps even beyond salvation. The system has gleefully cultivated this vicious instinct within us because it’s highly profitable, and will continue to be highly profitable, until we collectively agree we no longer accept this mode of existence as an unchangeable fact of life. The likelihood of this happening seems desperately slim, considering it feels inevitable that, as our attention spans continue to shrink, we’ll only grow more reliant on short clips for our news.

But let’s get back to Vance and his illusive pet-eating migrants: if you concede that what he really meant was that he wanted to push a narrative he believed was true, not create an outright fiction, then the NBC News interview could be seen as a prime example of the sound bite-centric media he’s railing against, because it leaves no room for an equally-plausible alternative explanation. The only narrative the “create stories” clip wants to sustain is “Vance admitted he’s a bold-faced liar,” which, of course, doesn’t allow for even the possibility that he simply failed to articulate what he really meant. It’s one of the more troubling aspects of the modern media landscape, the way networks carelessly disguise their inherent biases as objectivity (i.e. Fox News’ former motto being “fair and balanced”). Even so, it’s hard to blame the media for assuming bad intentions with Vance, because again, he has yet to provide hard evidence to support his claims. If pet-eating migrants are such a widespread phenomenon, as he asserts, where are the police reports and 911 recordings that purportedly exist? In a world where everyone has a camera in their pocket, not a single video or picture has surfaced so far as I’ve seen. Vance can complain about the media all he wants, and some of his laments are justified, but if he continues to make serious claims based on dubious hearsay, then why should the media, or anyone, give him the benefit of the doubt? The fact that he seems unwilling to dig deeper into the issue because he knows it likely reveal a truth incompatible with his partisan motives seems to prove that, as much as he likes to portray himself as an anti-establishment politician, he’s perhaps no different than the many two-faced characters who have inhabited the halls of power for as long as anyone can remember.

He says he wants to fight for common folk, that he wants to make groceries cheaper and support families, etc, but is he as actually committed to these initiatives, or are his words merely pragmatic rhetorical devices that he deployed to win an election, grab a slice of power and, alongside Trump, ultimately serve the desires of his white-collar cronies, including the richest man in the world, who seems to be more interested in colonizing Mars than improving life on Earth?

Furthermore, I’m highly skeptical, and think everyone should be, about who Vance will ultimately serve as a public figure on the national stage: as a guy with one foot in a working class upbringing and the other in the greed-obsessed world of venture capital, where do his strongest allegiances lie? With the blue collar folks living at or around the poverty line, or the billionaires he’s become buddy-buddy with? He says he wants to fight for common folk, that he wants to make groceries cheaper and support families, etc, but is he as actually committed to these initiatives, or are his words merely pragmatic rhetorical devices that he deployed to win an election, grab a slice of power and, alongside Trump, ultimately serve the desires of his white-collar cronies, including the richest man in the world, who seems to be more interested in colonizing Mars than improving life on Earth?

IV: I’m Exhausted From Thinking About J.D. Vance

Who is the real J.D. Vance? Is he a generally alright dude with decent intentions or a liar savant well-practiced at mimicking authenticity? Is he truly motivated by movements of his heart or a gifted opportunist who knows how to cloak his ambition in logic and pathos in an effort to gain power and convince people to like him? I felt a creeping sense of disingenuousness about his personality while listening to Elegy, when I couldn’t decide whether his frequent use of humility was a representation of how he actually felt about himself or a useful tool used to disarm critics. But perhaps asking “who is the real J.D. Vance” is the wrong question, anyway. Maybe it’s unanswerable, like “how many hairs do you have on your head?” Posing questions in the format of “is he this or that” belies how most human beings often exist in the world. We all contain the many, are different things at different times to different people. The truth of the matter, like most things, probably falls in the gray area: perhaps he’s both honest and deceptive, decent and repugnant, good-intentioned and devious, thoughtful and reactionary, sympathetic and callous. He, like all of us, contains multitudes, he’s just displaying those multitudes on an international stage. This is not an apology for his misgivings, and definitely not an endorsement of the guy. I’m only making judgments from a distance based on limited evidence, in an attempt to play devil’s advocate. How much could I possibly know about his soul?

I’ll park this sputtering excuse for a think-piece where I started it: unsure about whether Elegy a decent book, a harmful caricature, or both, and skeptical about the motives that rise and fall within Vance’s blue-collar, white-collar, baby-faced, bearded, pudgy, trim, Appalachian(ish), vice-presidential heart.

Alas, I think it’s time to bring this rambling piece to a close. I’ve gone on about Vance for 6,000 words now and am beginning to feel a sense of dread about failing to take us anywhere of consequence. I’ve allowed him to colonize far too much of my mental bandwidth over the past few weeks, and I have officially exhausted my capacity for thinking about the man. Elegy has been on near-constant repeat in my Prius for the better part of a month, and if I hear him say “APP-uh-LAY-shuh” one more time I’m going to sling all six CDs out the window, one-by-one, frisbee-style, at oncoming traffic. So I’ll park this sputtering excuse for a think-piece where I started it: unsure about whether Elegy a decent book, a harmful caricature, or both, and skeptical about the motives that rise and fall within Vance’s blue-collar, white-collar, baby-faced, bearded, pudgy, trim, Appalachian(ish), vice-presidential heart.

Is that an unsatisfying conclusion? Perhaps, but life is full of unsatisfying conclusions, and anyway we’ll be seeing much more of Vance over the next four years, so I suspect I won’t feel nearly as ambivalent about him in 2028 as I do now. Something has to give, one way or another, and when it does, I’ll be ready to pass scathingly inconsequential judgment from afar.

Further reading and listening

Leave a comment